Tim’s Turn: Family Time Will Always Flourish

The comment Leroy Gill, owner of Norumbega Park in Auburndale, Massachusetts, made in 1950 wasn’t as radical nor as innocent as it seems today. “When the average man and his family come to an amusement park now, they want relaxation, not noise and excitement,” he said. “Instead of noise and excitement, I give them peace and quiet.”

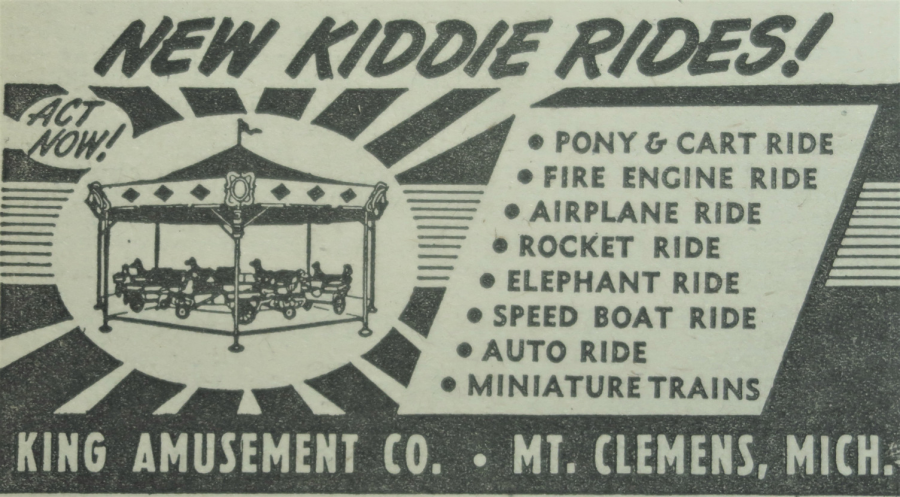

In a 1950 Billboard article, the 67-year-old Gill was billed as a genial, cigar-smoking veteran showman who built the park from a broken-down trolley park into a million-dollar property. Gill noted that the “moppet crowd has really taken over” and the kiddie rides they enjoy were just beginning to come into their own with a terrific potential, “while thrill rides are fading.”

As a journalist specializing in outdoor entertainment, I first started writing about amusement parks in 1985. Since then, I’ve seen all sorts of attractions, rides, and games that had “terrific potential” come and go within a few years. However, the quick rise in the kiddie ride business and the development of kiddielands across the nation was no flash in the pan. While most parks specifically created for the “moppets” evolved and dissolved during the 1950s, kiddie rides and specific kiddie areas within the major parks are still thriving, many serving as the backbone of the entire business. Gill felt that thrill rides weren’t on the minds of visitors because “A-bombs, H-bombs, jet fighters, and global wars have made the present generation thrill sated.” However, he went on to paint a futuristic picture of growth for attractions. “I predict that three-quarters of the amusement parks in the United States will be almost completely comprised of kiddie rides next season.”

You’ve heard the phrase, “history repeats itself.” Even before the pandemic, announcements of new thrill rides seemingly appeared less than in seasons past. Are parkgoers today once again overwhelmed by the state of the world that Gill pointed out, or is it a natural part of the ebb and flow of capital investments? I think it’s the latter. I’ve seen it happen many times before, when parks focus on families one year and the thrill ride group the next.

Nevertheless, looking back on Gill’s simple concept of 70 years ago is interesting. He decided to focus on families by adding smaller rides, baseball diamonds, swings, picnic tables, free movies on weekends, paddle boats, and canoes. His weekly attendance in 1950 was around 30,000, with an average of 12,000 to 15,000 on Sundays. In addition to the new emphasis on smaller rides, Gill made other areas of the park more family-friendly, as he interpreted the concept at the time. Liquor was not for sale and could not be brought in. No candy floss, candy apples, or candy of any kind was sold. Families were encouraged to bring in their own picnic baskets. Ice cream had to have 13% butterfat.

The park was built in 1897 on the banks of the Charles River on 37 heavily wooded acres. Gill felt the nature-oriented environment was conducive to families. There were more than 2,000 oak and maple trees, and he budgeted $4,000 a year to fill his 15 large flower beds. A separate landscaping budget led to the planting of hundreds of additional trees over the years. The park closed following the 1963 season; the land was subdivided, and a large Marriott was built on about half the property. The remaining land was taken over by the local government in 1975 and is now known as the Norumbega Conservation Area, a popular family-oriented recreation area. Families still enjoy picnics under the trees that Gill planted 70 years ago. Now, that’s a legacy.

Tim O’Brien is a veteran outdoor entertainment journalist and is a longtime Funworld contributor. He has authored many books chronicling the industry’s attractions and personalities and is the only journalist in the IAAPA Hall of Fame.