When guests go to parks and attractions, many of them grab the printed maps that are typically displayed at the entrance. However, Universal Orlando visitors discovered earlier this year that the once-ubiquitous maps at its parks were suddenly no longer available. Instead, guests were encouraged to download Universal’s mobile app and navigate the parks using the resort’s digital maps.

The switch to smartphone navigation is a trend that has been gaining momentum. As with road maps, landline phones, standalone cameras, and other longstanding conventions, the disruptive technology of smartphones has the potential to change the way guests navigate the environment around them.

Attractions.io, a U.K.-based mobile app company that develops branded maps for attractions, takes advantage of the surge of interest in transitioning to digital wayfinding. “Getting rid of printed maps can be a scary prospect,” acknowledges Jacob Thompson, head of customer success. Nonetheless, there are compelling reasons to make the move, including guest satisfaction improvements.

“Digital maps are a much quicker way to navigate, understand, and interact with a location,” Thompson says. “Operators can continually update and provide accurate, real-time info as well as target communications more strategically,” he adds.

When ZooTampa in Florida contacted Attractions.io about developing a mobile app in 2019, the conservational organization was concerned about environmental stewardship. It was printing hundreds of thousands of paper maps, a practice that was not aligned with its sustainability goals. The company created an interactive digital map for the zoo, and orients itself based on the user’s position, providing intuitive wayfinding directions. It was a hit for both the zoo and its guests.

“By phasing out maps as well as tickets and membership cards, ZooTampa reduced unnecessary paper waste by 95%,” says Thompson. “Not only was it much more sustainable, it saved them close to $50,000 a year in print costs. The zoo put the savings into manatee conservation initiatives.”

Among Attractions.io’s other clients that recently made the switch to digital maps are San Diego Zoo, Djurs Sommerland theme park in Denmark, and Yorkshire Wildlife Park and Chester Zoo, both located in England.

By 2026, digital natives—an identifier for individuals born into a world of computers and smartphones—will make up the majority of consumers. But what about those guests, even though their numbers are small, that don’t own a smartphone? Or folks that have a device, but are not particularly savvy with technology?

While ZooTampa significantly reduced its printed maps, it didn’t eliminate them completely. Guests can still request and receive a paper map, although they are hidden from view.

On the other hand, Village Roadshow Theme Parks (VRTP), which includes Warner Bros. Movie World, Sea World, Wet‘n‘Wild, and Paradise Country, discontinued printing all park maps in 2019, after it launched its company-wide app. As with ZooTampa, conservation concerns initially drove the switch.

“We had trialed the move away from a printed map initially at Sea World as part of our responsibility to reducing our impact on the environment,” explains Bikash Randhawa, chief operating officer at VRTP.

When the move received positive guest feedback, the company introduced digital maps at all its Australian parks. Using beacons throughout the parks, the phone-based maps can incorporate other features, including ride wait times, updates, alerts, and targeted offers. Randhawa says that there were some initial pockets of resistance when VRTP stopped printing maps, but it ultimately proved to be an easy transition. The biggest obstacle, he notes, is the sentimentality that the paper maps engender.

“While there is a small nostalgic element of losing a printed park map as a souvenir, the benefits of moving towards a digital map far outweigh the challenges,” Randhawa says.

Efteling in the Netherlands is slowly phasing out its printed maps. Over the last few years, it has reduced the number of paper maps by nearly 50%, according to Karin Koppelmans, who handles the park’s communications and corporate affairs. The maps are still available but are displayed in a less prominent location. Posters at the entrance and inside the park encourage guests to use Efteling’s app.

“As for plans to stop using [printed maps] altogether, that’s still a bit tricky, considering our many crooked paths and organic layout,” she says about the park that was founded in 1952.

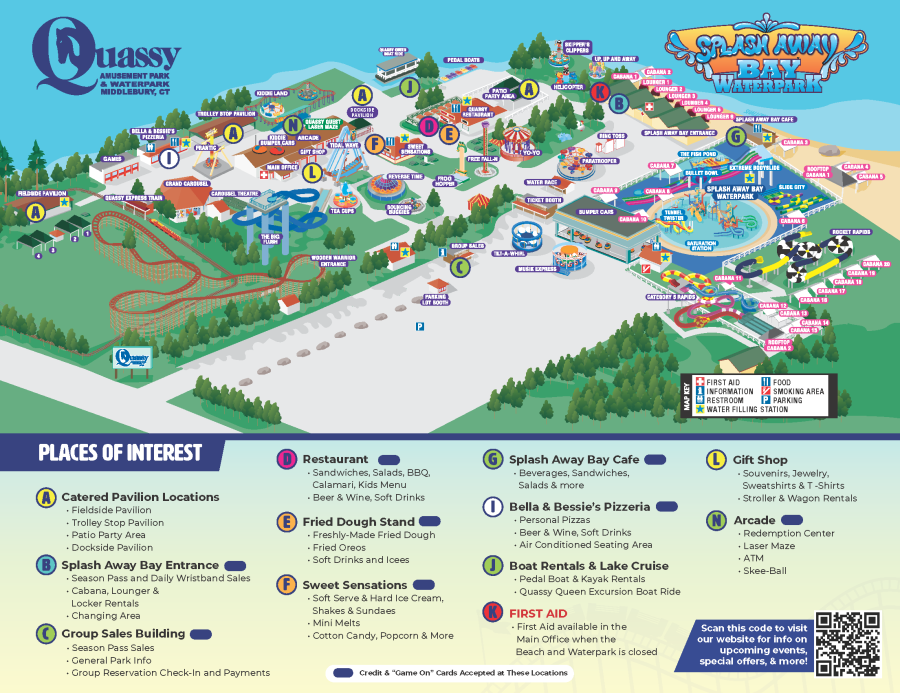

There are still a number of holdouts who do not have phone apps. Quassy, the historic amusement park in Connecticut, for example, distributes flyers to guests that include a park map. The handouts include a QR code that users can scan to download a static map to their devices. Co-owner George Frantzis says Quassy currently has no plans to discontinue the printed maps or introduce an app.

Paper maps are “a nicety, kids like them, and they offer sponsorship opportunities,” he notes.